Jan Hus hoped his incendiary preaching and heated rebukes would purify a tainted church, but the flames consumed him first.

by Dr. Thomas A. Fudge

Constance, Germany, Saturday, July 6, 1415.

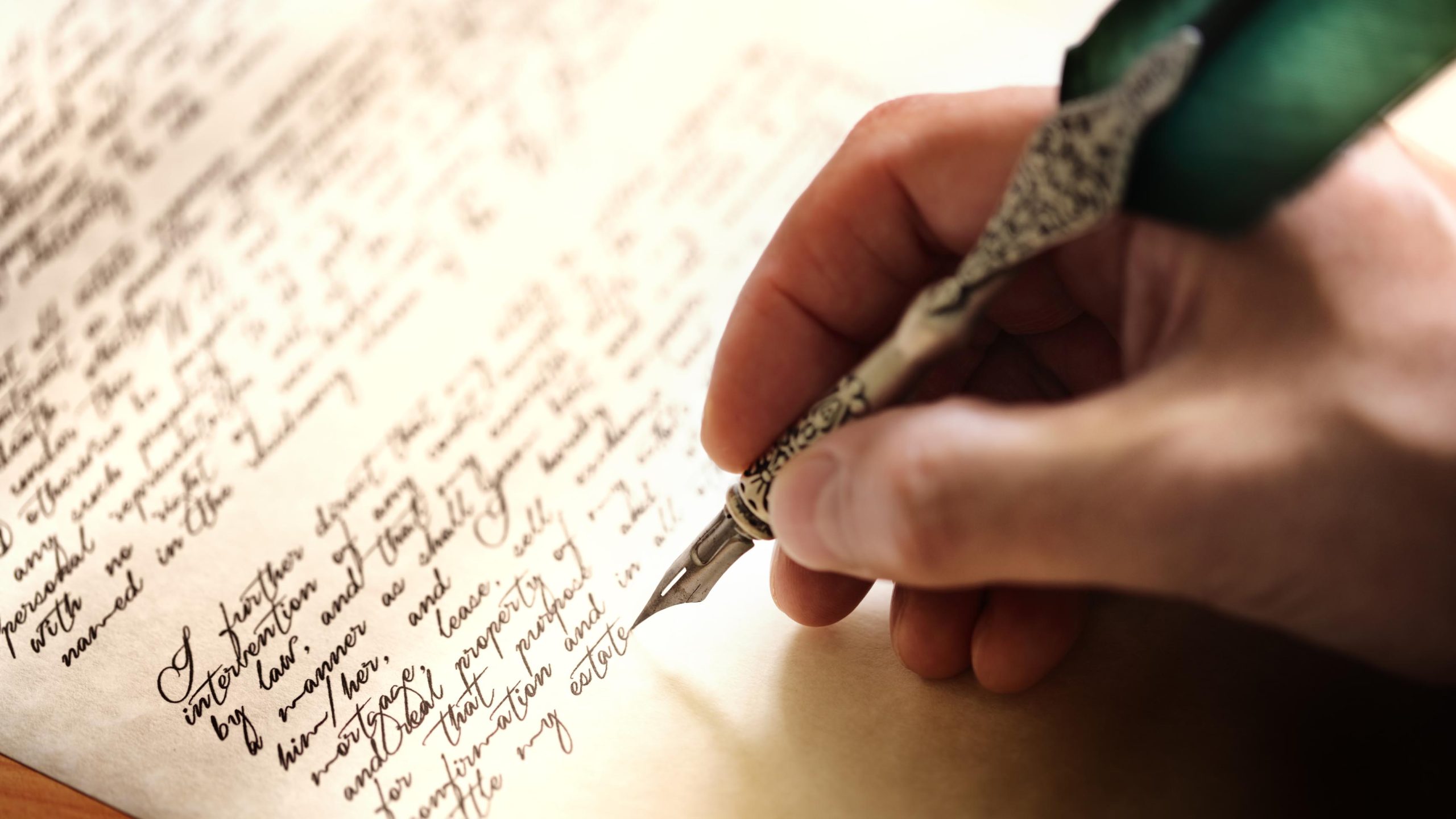

Konstanzer Münster – where Hus’ trial was held.

The cathedral was packed to the doors. A hot heaviness hung in the air. Jacob Balardi Arrigoni, Bishop of Lodi, was preaching from the text, “that the body of sin be destroyed” (Romans 6:6). Cardinals with red hats and bishops wearing miters sat in a semi-circle around a dying man whose chained, emaciated hands were clutched together. Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund occupied an imperial throne in full regalia. In the nave a variety of priestly garments had been carefully laid out on a table.

There were now only two options left open to the man in chains: unqualified submission to the council or condemnation. Recant or die.

The stake stood ready outside.

Peasant provocateur

Forty-three years earlier, Jan Hus had been born far from the shores of Lake Constance. He took his name from his hometown, the village of Husinec in southern Bohemia (today part of the Czech Republic). In Czech the word “hus” means “goose,” and Hus often punned on his own name.

His parents were peasants—nameless and unknown. His mother taught Jan to pray and, as he grew older, influenced him toward a career as a priest.

Though Hus admits he originally pursued priesthood for the money and prestige, his spiritual zeal grew as he studied. In 1393 he spent his last bit of money to buy an indulgence, a certificate granting him forgiveness of sins. Hus recounts his poverty while studying at the university in Prague: “When I was a hungry young student, I used to make a spoon out of bread in order to eat peas with it. Then I ate the spoon as well.”

Bethlehem Chapel in Prague, where Hus preached in the common language.

Hus was not a brilliant student, and his university career was unexceptional, though he received a master’s degree in 1396. He became well known in 1402 when he was appointed preacher in the Bethlehem Chapel in Prague, a church founded in 1391 to provide preaching in the common language.

Shortly before Hus’s appointment to the Bethlehem Chapel, the influence of English reformer John Wyclif reached Bohemia via Czech students who had spent time at Oxford. Hus found in Wyclif a philosophical framework for the practical ideas of the Czech reform program. “Wyclif, Wyclif,” he wrote in the margin of a manuscript, “you will turn many heads.”

Not everyone agreed. Prague University, where Hus taught in addition to his pastoral duties, soon split down the middle. The German masters agreed with Wyclif’s 1382 condemnation by the Blackfriar Synod in London, while the Czech masters supported Wyclif’s call for more scriptural teaching in the vernacular and less deference for church hierarchy, since the Roman curia was largely corrupt anyway.

Another major point of contention was transubstantiation. The Germans and other Roman Catholics strongly supported the doctrine, while many Czechs and other “Wyclifites” argued for remanence—the idea that the bread and wine remain unchanged after consecration. Hus never adopted this radical view, though he was repeatedly accused of it later.

Here a pope, there a pope

The debates about Wyclif were overshadowed by an even bigger church battle, the papal schism (1378- 1417). Hus never took a direct role in this conflict, but two men with power over his fate did: King Václav IV of Bohemia and Zbyněk, Archbishop of Prague.

King Václav IV (sometimes called Wenceslaus) was vacillating, unpredictable, and probably mad. He drank far too much, frequently flew into fits of rage, and was notorious for naming incompetent advisers.

Václav’s 41-year reign (1378—1419) spiraled consistently downward. He interfered in ecclesiastical affairs, committed numerous administrative blunders, alienated members of his own family, and was a conspirator to torture and murder. His first wife died after being mauled by his dogs, which he insisted on keeping in his bedchamber.

Coat of Arms of Archibishop Zbyněk Zajíc of Hazmburk

Václav did have one good adviser: his second wife, Žofie, who understood him perfectly. At their wedding, she presented him with a wagon load of conjurers and juggling fools, which pleased him enormously. Queen Žofie attended Hus’s sermons in Bethlehem Chapel and used her influence in Bohemia to facilitate Hus’s reforms.

The other leading man in the kingdom was Hus’s spiritual superior, Archbishop Zbyněk, a military man wholly unsuited for the spiritual life. In 1402, when he was 25, he outbid other contenders and bought the archbishopric of Prague for the sum of 2,800 gulden. Though pious and well-meaning, at least initially, he had almost no theological training and lacked any sense of church administration.

Zbyněk did not understand the debates that gripped the university, and for a while he seemed to take little notice. However, Wyclifism had been declared heretical before Zbyněk took office, and as the papal schism dragged on, the presence of heresy in Bohemia became a momentous concern.

Václav hoped that if he could ally himself with the right papal contender and take a leading role in ending the schism, he might win back the title of Holy Roman Emperor, which he had lost in 1400. In 1409 he shifted his support from the Roman pope, Gregory XII, to the newly elected Pisan pope, Alexander V.

Zbyněk’s job was to eradicate heresy at home, removing any obstacle to Václav’s election as emperor. But Zbyněk resented the king’s changing allegiance, and he refused at first to recognize Alexander V. Furthermore, Wyclifite “heresy” and church corruption were everywhere in Bohemia—and Hus made sure everyone knew it.

Hard words for “fat swine”

While church and state clashed over which pope to endorse, Hus had forged ahead onto dangerous ground. In 1405 he denounced alleged appearances of Christ’s blood on communion wafers as an elaborate hoax. His sermons condemned the sins of the clergy. He ridiculed the power some priests claimed for themselves when they called their parishioners “knaves” and declared, “We can give you the Holy Ghost or send you to hell.”

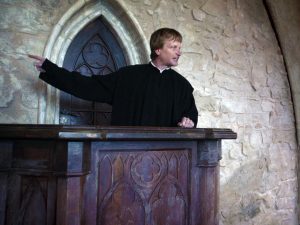

Matěj Hádek portrays Jan Hus in the 2015 movie. Courtesy of Česká televize.

Hus roared against such abuses. “These priests deserve hanging in hell,” he said, for they are “fornicators,” “parasites,” “money misers,” and “fat swine.” “They are drunks whose bellies growl with great drinking and are gluttons whose stomachs are overfilled until their double chins hang down.” The appalled clerics began to murmur against Hus.

Lashing out at widespread simony (the practice of buying spiritual office), Hus condemned Prague’s wealthiest clergy—”the Lord’s fat ones,” as he called them—for charging steep fees for administering sacraments and for taking multiple paid positions without faithfully serving any. While claiming apostolic succession, they bore no resemblance to the apostles.

Hus put these words into the mouth of Christ: “Everyone who passes by, pause and consider if there has been any sorrow like mine. Clothed in these rags I weep while my priests go about in scarlet. I suffer great agony in a sweat of blood while they take delight in luxurious bathing. All through the night I am mocked and spat upon while they enjoy feasting and drunkenness. I groan upon the cross as they repose upon the softest beds.”

The reaction came swiftly. Archbishop Zbyněk, openly guilty of simony and aware that publicized reports of immoral clergy made him look bad, took steps to silence some of Hus’s supporters who had violated customary practice by preaching without permission.

Hus objected and accosted the archbishop: “How is it that fornicating and otherwise criminal priests walk about freely … while humble priests … are jailed as heretics and suffer exile for the very proclamation of the Gospel?”

This was too much for church officials. Spies were placed in Hus’s chapel to report on his preaching. Once, in mid-sermon, Hus spotted one of them.

“Hey, you in the hood, make a note of this, you sneak, and carry it over there,” he said, pointing in the direction of the archepiscopal residence. Hus was cited before a hearing. He successfully defended himself, enjoying support from the crown and the public, but the archbishop was now his sworn enemy.

Catching a goose

Zbyněk was forced eventually to submit to the king and support Alexander V. The beleaguered cleric had now lost both to Hus and Václav, and he was hungry for revenge.

Zbyněk complained bitterly to Pope Alexander V, begging for action against his enemies. A papal bull was published calling for an investigation into the potential heresies of Wyclif and Hus and demanding that preaching in private chapels cease. Essentially the pope censored Bethlehem Chapel.

Hus spoke publicly against the bull, and more than 2,000 worshipers declared their willingness to stand with him against the archbishop and the pope. The king made no comment, because he needed the archbishop on his side.

Zbyněk went on the offensive. Hus describes an attempt to destroy Bethlehem Chapel while he was in the pulpit preaching: “Led by Bernard Chotek, clad in armor, with crossbows, halberts, and swords, they attacked Bethlehem while I was preaching … wishing to pull it down having conspired among themselves.”

The attempt was abortive. Plan A having failed, the archbishop implemented Plan B. He gathered as many copies as he could find of the works of John Wyclif and hauled them into his palace courtyard. On July 16, 1410, with gates tightly barred, bells tolling, and priests singing the Te Deum, Zbyněk ordered the pile of books set ablaze. More than 200 volumes became ashes.

Fearing a backlash, the archbishop fled to his fortified castle in Roudnice, about 30 miles north of Prague. The reaction was severe—people rioted, made posters ridiculing Zbyněk, and scorned him in popular songs: “Bishop Zbyněk, ABCD, burned books not knowing what was written in them.”

Hus responded forcefully: “I call it a poor business. Such bonfires never yet removed a single sin from the hearts of men. Fire does not consume truth. It is always the mark of a little mind that it vents its anger on inanimate objects. The books which have been burned are a loss to the whole people.”

Feeling safe behind castle walls, Zbyněk excommunicated Hus. Two months later Hus was placed under “aggravated excommunication,” but he continued to preach and go about his duties, paying little heed to the bulls. He had far more support in Prague than the archbishop did.

Vaclav IV (Wenceslaus) King of Bohemia

When the pope stalled in pursuing the Hus case, Zbyněk sent generous gifts. These were distributed at the papal court, and a third notice of excommunication was issued against Hus in February 1411.

Riding the crest of papal support, the archbishop took another step to consolidating his fragmented power. He excommunicated royal officials in Prague on May 2, 1411. It was a fatal move.

Silent for so long, King Václav awoke from his drunken stupor and told Zbyněk to back off. Head to head, like implacable warriors, the king and the archbishop tried to stare the other down. The king called the archbishop’s bluff.

Zbyněk played his last card and placed Prague under interdict, suspending all church activities—marrying, burying, blessing, preaching, administering Communion. Though this was a powerful weapon, Václav did not blink. The magistrates supported the king. The fight was over. Zbyněk had no alternative but to relent and declare obedience to the king.

The archbishop was required to declare all proceedings against Hus null and void. A writ terminating all action against him was to be obtained from Pope John XXIII (the new Pisan pope, elected after Alexander’s sudden death). Hus and his followers were ordered cleared of all heresy, and the archbishop was scheduled to make a public declaration to that effect.

Before these steps could be implemented, however, Zbyněk died under mysterious circumstances. Rumors suggested murder. It was a most inconvenient time to die.

On the brink of Hus’s vindication, papal proceedings moved to another level. Hus was summoned to appear in Bologna. The king forbade it. “If anyone wants to accuse Hus of any charge, let them do it here in our kingdom. … [I]t does not seem right to give up this useful preacher to the discrimination of his enemies.”

Queen Žofie surely prompted Václav’s action. She also took up the pen and in October and November 1411 posted letters to the papal see requesting that “the faithful, devout and beloved Hus,” whom she calls “our chaplain,” continue to have freedom to preach the gospel.

The queen’s sincerity was genuine, but the king’s support was contrived and politically expedient. Žofie’s support would not waver even at the end, but Václav’s could be counted on only as far as Hus remained politically useful. That usefulness was limited.

The indulgences game

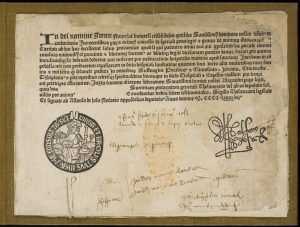

In 1412 Pope John XXIII proclaimed a crusade against the king of Naples, who had seized control of Rome. To raise the funds, the pope instituted a large-scale sale of indulgences. Revenue raised in Bohemia would be shared with the king, so Václav stood to profit from their sale. Three of the principal churches in Prague became indulgence purchasing centers.

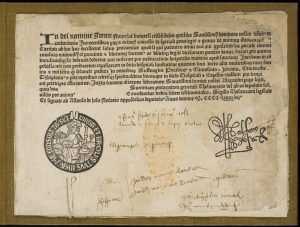

Papal Indulgence, circa 1498.

Hus was outraged and preached against the practice, charging that the operation supported brothels, taverns, and priests living with girlfriends. He called for a boycott.

Hus was cited to appear before the newly elected archbishop of Prague, Albík. He refused to submit or modify his language. “Even if the fire to burn my body were placed before my eyes,” he said, “I would not obey.”

His enemies continued to gather ammunition, but Hus remained defiant. “Shall I keep silent? God forbid! Woe is me, if I keep silent. It is better for me to die than not to oppose such wickedness, which would make me a participant in their guilt and hell.”

Seeing his revenue stream beginning to slow, the king ordered Hus to submit to ecclesiastical authority. Hus demurred.

At this point, the radical influence of Wyclif comes into clear focus in Prague. Wyclif already had denounced the papacy in strident and provocative terms: “In a word, the papal institution is full of poison, antichrist himself, the man of sin, the leader of the army of the Devil, a limb of Lucifer, the head vicar of the fiend, a simple idiot who might be a damned devil in hell, and more horrible idol than a painted log.”

Hus’s friend Jakoubek of Stříbro joined the chorus declaring the pope antichrist. The indulgence controversy turned bloody, and protesters were summarily executed.

With royal revenue now in serious doubt, Václav breathed an ominous threat: “Hus, you are always making trouble for me. If those whose concern it is will not take care of you, I myself will burn you.” Even Žofie was powerless to stay the rage of the mad king.

Hus was excommunicated for the fourth time, and Prague was again placed under interdict. This time the king did not intervene.

Unwilling to deprive the city of church ministrations, Hus voluntarily went into exile on October 15, 1412. For two years he labored in the villages of southern Bohemia, writing books and preaching in barns, fields, towns, and forests.

Then, in the fall of 1414, Pope John XXIII convened an ecumenical council in Constance, and he invited Hus to attend. The conciliar fathers gathered with two purposes: end the papal schism and eradicate heresy from the Western church.

Ambush

Hus accepted the invitation. On October 11, 1414, riding on his “strong and high-spirited” horse Rabštýn, he departed for the council. His friends warned him he might be walking into a trap, but Emperor Sigismund, Václav’s half-brother, had promised Hus safe conduct, and Hus believed him.

When Hus arrived in Constance, he was optimistic, sending a letter to friends joking that “the goose is not yet cooked and is not afraid of being cooked.” The next week he was thrown into prison, where he languished for several months while the council addressed other matters.

Hus’s health declined precipitously in the terrible conditions of the Dominican prison where his dark, damp cell, hard by the latrines, was filled with awful stench. Only a visit from the pope’s physician and relocation to a better cell spared Hus’s life.

Hus’s enemies in the council were caustic. According to one, “Since the birth of Christ there has never been a more dangerous heretic than you, with the exception of Wyclif.” Others insisted that the “Czechs were unworthy of the name Christian.” Hus was singled out as the chief heretic and his ideas declared as inimical to the faith as the “Koran of Mohamed.” To his judges Hus was quite simply a “wicked man.”

Hus’s friends rallied around him, imploring Sigismund to honor the safe conduct. They smuggled letters and documents out of the prison. Since Václav seemed to have forgotten his suffering subject entirely, Czech noblemen signed their names and affixed their seals to numerous formal protests over the treatment of Hus. After receiving the letters, the council in Constance cited 452 nobles to appear. Not one obeyed.

At the hearings, Hus was refused opportunity to defend his ideas or reply to specific charges. Attempts to argue his case resulted in shouts from the conciliar fathers that Hus was arrogant and stubborn.

An old, bald, Polish bishop asserted that the law was clear on how to deal with heretics. Another priest shouted, “Do not permit him to recant; even if he does recant, he will not keep to it.”

Sigismund, far from upholding his promise of safe conduct, acquiesced privately in the opinion that Hus was the greatest heretic ever to have arisen in Christendom and therefore deserved no protection.

“The case of Jan Hus ought not to interfere with the reform of the church and empire, which is the principle purpose for which the Council has been convened,” he said. “For myself, I wish to stand by the holy church; I do not incline to like new ideas.”

In this uproar, Hus was led out of the council chambers and back to his cell. His friend, Lord Jan of Chlum, courageously stepped forward and shook Hus’s hand in full view of the assembly.

Later, Jan of Chlum urged his friend to recant and save his life. “But if, indeed, you do not feel guilty of those things charged against you,” he said, “follow the dictates of your conscience. Under no circumstances do anything against your conscience.” Hus followed only the latter advice.

The last session of the Hus case was held July 6. Thirty final charges were presented against the indicted heretic. Some were preposterous—one declared that Hus taught he was the fourth person in the Godhead!

Hus rejected all charges, but his attempts to speak were shouted down. He did not realize he was doomed. Sigismund had already warned the court that even if Hus recanted, the recantation should be dismissed, because Hus could not be trusted.

The warning was unnecessary, for Hus refused to recant on the grounds that he had never taught the errors ascribed to him. To do so would be to commit perjury: to lie. Instead, between interruptions, he refuted the council’s accusations by telling them their facts were wrong.

Pierre d’Ailly, the presiding cardinal, advised Hus to submit to the council. In a fatherly tone, he gave Hus two options: “Either you throw yourself entirely and totally on the grace and into the hands of the Council… or, if you still wish to hold and defend some articles of the forementioned, and if you desire still another hearing, it shall be granted you.” Then d’Ailly counseled strongly against the latter option. It really did not matter; any hint of mercy was a sham.

When Hus asked to be shown his errors from Scripture, the bishops dismissed him as “obstinate in heresy.” The council assembled the 30 heretical articles Hus supposedly held, ignored Hus’s assertions that he had never taught or believed the doctrines, and sentenced him to death.

Hus assented to the method, telling his friend Jan of Chlum that he preferred to be burned publicly rather than silenced in private “in order that all Christendom might know what I said in the end.”

To the fire!

The Archbishop of Riga led Hus to the cathedral door. Hus protested. Cardinal d’Ailly ordered him to “be silent.” Hus persisted. Cardinal Zabarella rose, saying, “Be silent now. We have heard enough already.” He then ordered the guard, “Force him to be still!”

As Hus fell to his knees on the stone floor, praying, his books were condemned to be burned. Hus wished to know if they had even been read but was met by a volley of shouts demanding silence. Hus appealed to God, and the council declared that such an appeal was erroneous because it contravened canon law.

When Hus prayed aloud that Christ might forgive his judges and accusers, many of the fathers of the council looked indignant and jeered.

Hus declared he had come willingly to the council under imperial safe conduct. As he made these remarks Hus turned to face Sigismund, who looked away.

The council made its final offer: “Recant or die.” With those words ringing in his ears, Hus turned his face from his judges and prepared for his final journey on earth.

When the Bishop of Lodi concluded his sermon on destroying the body of sin, seven bishops dressed Hus in the priestly vestments that had been set on the table. Then he was defrocked.

In turn a different bishop tore each of the vestments from Hus’s body, saying, “O cursed Judas … we take from you the cup of redemption.” They removed the stole, the chasuble, and all of the vestments with appropriate curses concluding with the words, “we commit your soul to the Devil.”

Hus was crowned with a paper miter upon which were three demons and the inscription: “This is a heresiarch.” Accompanied by a multitude, Hus was then pushed through the streets of Constance to the place of death.

He was bound to the stake with a sooty chain wrapped around his neck. Wood was piled to his chin. Hundreds of men, women, and children thronged restlessly.

Hus was given one final chance to save his life by recanting all his errors and heresies. A pause fell over the meadow, then Hus’s voice could be heard clearly: “God is my witness that … the principal intention of my preaching and of all my other acts or writings was solely that I might turn men from sin. And in that truth of the Gospel that I wrote, taught, and preached in accordance with the sayings and expositions of the holy doctors, I am willing gladly to die today.”

An audible murmur rippled. The signal was given. The executioner set the pyre ablaze. From the smoke and flames that shot upward into the summer sky, Hus’s voice could be heard once more, this time in song. “Jesus, son of the living God, have mercy on me.”

In the midst of the billowing flames, witnessed by an incredulous crowd, Master Jan Hus sang these words three times. The goose was cooked. He died singing.

Thomas A. Fudge is senior lecturer at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, and author of The Magnificent Ride: The First Reformation in Hussite Bohemia.